By Matthew Cimitile, University Communications and Marketing

Juneteenth has become the most well-known celebration for the ending of slavery in the United States and viewed by some as America’s second Independence Day. But the history of this important celebration is complex and often misunderstood.

Juneteenth isn’t a straightforward story of emancipation, nor did it necessarily improve conditions for many African Americans the next day or even the next decade, according to Erin Stewart Mauldin, the John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History at USF St. Petersburg and an expert on the Civil War and Reconstruction.

“Juneteenth is neither the beginning nor the end of something,” Mauldin said. “The end of the Civil War and the ending of slavery didn’t happen overnight and was a lot more like a jagged edge than a clean cut.”

Dating back to 1865, the holiday commemorates the day when 250,000 slaves in the state of Texas, which became the last bastion for slavery during the final days of the Civil War, were declared free by the U.S. Army.

As soon as the following year, local festivities were organized in African American communities to celebrate and remember the significance of that day, June 19. The celebrations continued year after year.

In the 20th century, as African Americans from Texas and neighboring states spread throughout the country, so too did Juneteenth celebrations. In 1980, Texas became the first to make it a state holiday. Shortly thereafter, other states followed suit, along with organizations and businesses across the nation hosting events and educational opportunities dedicated to commemorating the significance of this day.

In 2021, the day became a national holiday.

Emancipation & the fight for justice

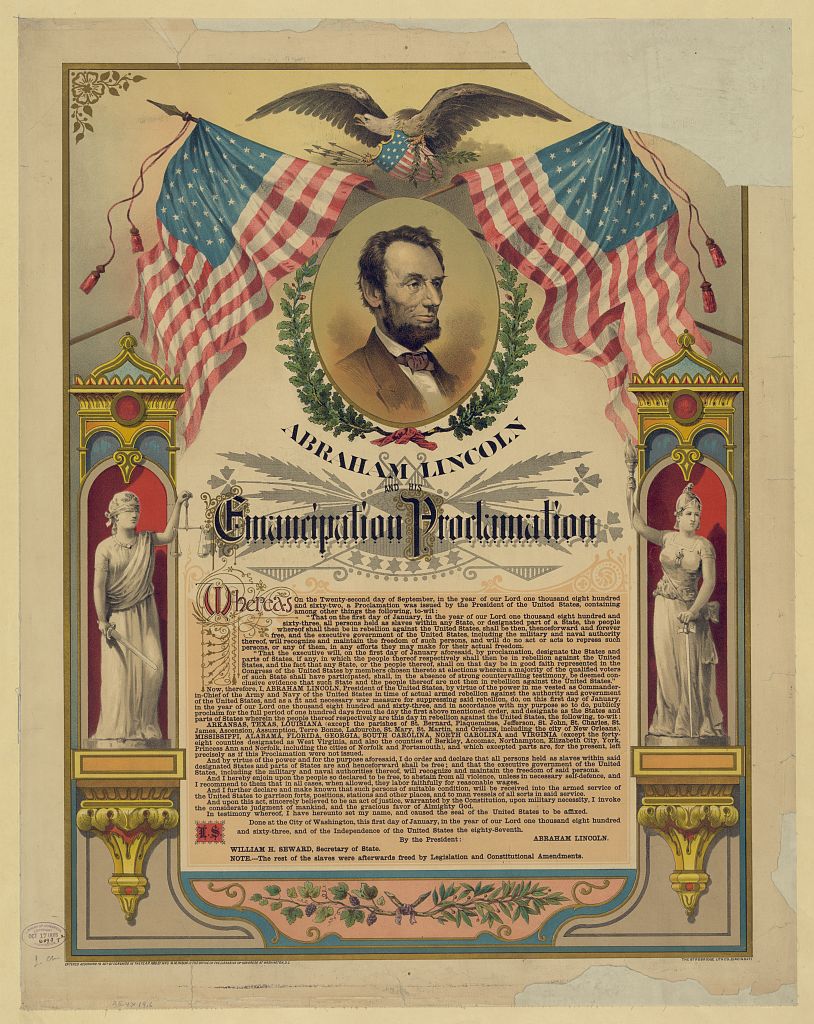

Some slaves in the Confederate states were technically freed as early as January 1, 1863, the date when the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Abraham Lincoln and went into effect. The proclamation was only as good as the Union army’s enforcement of it (and didn’t pertain to slaves in the Union border states of Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland and Missouri), meaning slavery ended in a region when the army occupied the territory.

Even after General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate Army, surrendered at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, an event generally regarded as the end of the Civil War, battles, skirmishes and slavery continued. The last Confederate holdouts moved further away from the approaching Union army as possible, ending up in Texas.

The Emancipation Proclamation. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division).

“When Lee surrendered at Appomattox, it’s not over. Major military campaigns went through June and people continue to fight for years,” Mauldin explained. “Depending on how isolated the enslaved were from the U.S. army or networks of information or places they could escape to, bondage did not end in 1865.”

From there, the story becomes even more complicated. Now free, the formerly enslaved had no wealth, no property and few places to turn. The best solution for many was staying where they were, working for former slave owners and fighting to ensure they would now get paid in a new arrangement of employer and hired labor.

“Plantation owners didn’t want to pay their former slaves at all and the former Confederate states were more or less broke after the war, so they didn’t have money to even pay,” Mauldin said. “Though slavery ends, the conditions for many change very little initially.”

Eventually contracts would become standardized among employers and labor and an economic system of sharecropping developed. Laborers would work a plot of land for a share of the crop or profits at the end of the year. Some would begin to amass goods and property, enough to make their own decisions on what to plant, what livestock to buy and even hire additional laborers to farm the land.

But many in this new economic system would amass debt, as the only way to receive property and items to farm was to become indebted to landowners. The struggle for freedom morphed into a struggle for economic independence.

“Freedom was not a straight line from the Emancipation Proclamation to Juneteenth to the Civil Rights movement,” Mauldin said. “Individuals had to fight for every piece of freedom they experienced and the struggle for justice that started long before the war did not end with emancipation.”

The celebration of Juneteenth today is important because it helps initiate difficult conversations and raises awareness about the country’s complicated and tragic history of slavery, Mauldin said.

“It is immensely important to remember the difficulties of fighting and securing even the smallest measures of freedom,” she said. “Juneteenth has become a symbol for emancipation and provides a highly visible celebration that does get at these difficult conversations about America’s history.”

Emancipation celebrations in Tampa Bay

The first celebration of emancipation in Tampa even precedes that of the first recorded Juneteenth, based on research by Professor Mauldin.

On May 6, 1864, federal forces including Black soldiers of a colored regiment recaptured Fort Brooke in Tampa from the Confederacy, liberating the enslaved in the city. The following year, several Black farmers borrowed American flags from federal units still stationed in the city and marched through Tampa to commemorate their freedom, according to local newspaper accounts.

John Donaldson was the first black settler in St. Petersburg. Courtesy of Pinellas County Historical Society.

Since then, the Black community in Tampa would celebrate their Emancipation Day in May, typically with a festival that included a community-wide picnic.

Across the bay in St. Petersburg, the first Black family didn’t settle in the city until 1868. The first recorded celebrations in newspapers of emancipation weren’t until the turn of the 20th century, and largely coincided with the ratification of the 13th Amendment or when the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, which occurred on December 6 and January 1 respectively. St. Petersburg's celebrations were typically sponsored by local Black churches and civic organizations, featuring worship services, marching bands, literary programs and speeches by prominent guest speakers.

As they evolved, Emancipation Day celebrations in Tampa Bay would reflect the social and political concerns of Black residents of the time. When communities would celebrate those festivities reflected the local history of when emancipation occurred.

“Juneteenth is the national date we have chosen, but each city, county and state celebration of emancipation differs because of when federal troops arrived or when hostilities ceased and those enslaved were liberated,” Mauldin said.

General Order No. 3 from Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger, freeing the slaves of Texas on June 19, 1865 (known today as Juneteenth)

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere."